Pricing strategy and tactics

Pricing strategy is crucial to initiating enquiries and achieving sales at the close.

Effective pricing strategy that navigates the circumstances of a market is often overlooked by many companies which instead rely on cost plus procedures or simply attempt to undercut the competition.

Below introduces some of the variables involved when developing results driven pricing strategies from a marketing perspective.

Pricing using market positioning

The price you charge is dictated by how much a potential customer is willing and able to pay for your product or service; given the offer and price of alternatives such as competitor products or not buying at all.

Your pricing strategy is dictated by your wider business strategy in that you have to define and execute what you have determined to be your market proposition and positioning.

Competition products are defined here as direct competition (competitors offering similar products: example Coca Cola v Pepsi) or substitute products (products that can be substituted by something else: example Coca Cola v water).

For example: people choose to buy Coca Cola over just drinking water due to the added value of taste sensation and brand.

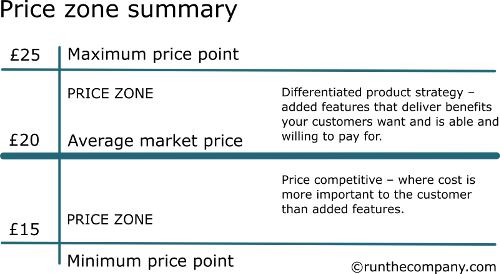

Price zone based on product features and benefits

Product A has features and benefits that adds meaningful value to the customer user experience.

Price £100

Product B provides the minimum requirement for the customer to use the product for which it is intended.

Price £60

The price difference between these two products is £40. From your premium product perspective, this is a positive price differentiation.

The price zone is the difference in price a customer might be willing and able to pay given the additional features and benefits your product offers.

You have to determine if this is true or can be true given your intended marketing strategy and activities.

You may determine your product price could be more; in this case £120 or even £180. The assessment should be on the price zone and not the maximum price point itself.

The question you ask therefore is not just would your customer be willing and able to pay £100 for your product but would they be willing to pay £40 more than that available from the competition.

Price zone based on branding

Product A has an in-vogue brand presence in the market.

Price £100

Product B offers the same features and benefits but does not possess a brand entity.

Price £60

There are brands in certain sectors (such as clothing retail) that are successful at a premium price. The function of a tee-shirt is to cover the upper part of the body. The meaningful added value benefit is the feel good factor of wearing a brand on the upper part of the body.

Being more expensive, even reassuringly expensive, confirms the brand positioning. How long the life cycle is for the brand is another matter. Tee-shirts will likely be around much longer than the brand.

When lower price does not sell

Sometimes a lower price positioning can surprise you in that competitors with higher prices still sell and you don’t. Value for money is often a perception based on known information and brand loyalties.

Types of propositions and effective influence on price

Do not attempt the positive price point (be more expensive than the competition or expensive enough to strain your customer’s ability to pay) based only on the generic proposition of quality and service. This lacks a substantive definition and rarely works.

Focus and define the added benefit to justify the premium price.

Product features

Additional product features that deliver benefits the customer considers important is the single most effective justification for a positive price point (being more expensive than your competition). The key here is perceived and wanted value.

Product quality

The problem here is that the proposition of inert or generic quality is often retrospective in that the customer does not always appreciate the lack of quality until the product breaks down or wears out quicker than expected. The customer may not buy another for a long while or may even be disillusioned by such products or believe they all malfunction regardless of who supplies it.

Frequency of purchase is more relevant to product quality in that the customer is likely to try other suppliers and even pay more for the product when the inconvenience of malfunction becomes a motivation.

Convincing customers of product quality can often require defined and inventive marketing. An educated market may comprehend and appreciate the importance of a defined quality. In this case a defined quality does become a differentiated product benefit demanding a higher zone price.

This will likely still require marketing that communicates why the product possesses a defined quality that is worth paying more for, along with justifications (using the magic “because” word – it is this because of that).

Avoid generic terms such as best or better quality: generic terms mean nothing.

The exception might be touch/feel purchases or purchases where quality can be determined before the purchase.

Price points and increasing or diminishing returns

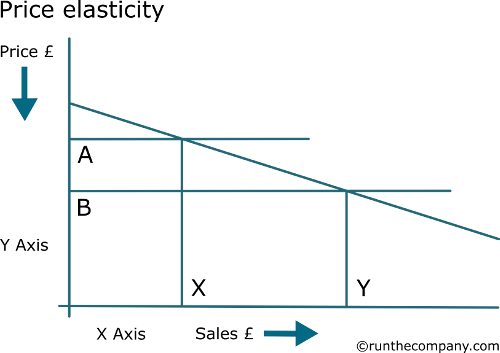

Below is a simple graph demonstrating how reducing price may increase total sales.

The usefulness of this graph is more about insight rather than application. The reasons are explained below.

As you reduce price from A to B, your sales increase from X to Y. The ratio between price points and the extent to which the market reacts is called Price Elasticity. This principle is found in most Economics school text books. How it applies to you in the real world depends on a number of other factors – all of which can strengthen or diminish the relationship between the X and Y axis on this graph.

How strong the link is between the Y axis and X axis depends on:

- How strong the communication channels are to tell your prospects about your price.

- How strong your message is.

- How relevant the price is given differentiated product propositions.

- Potential responses by competition. For example, you may reduce your price on Monday, expecting new sales volume at Y in the graph; only to discover your competition has responded with their lower price on Tuesday.

Somewhere on the line is an optimum point where price x sales provides the maximum profit – given all variables.

So here are the extremes:

- Set your price point too high and your sales will reduce and your market share will be handed to your competition.

- Set your price point too low and you may encounter cash flow and scaling problems and/or become a busy fool – working hard for little or no profit.

Price-lead markets

Limited scope for differentiated products

If you are marketing products where features beyond functionality are not important then these can be loosely termed as commodities. Commodity products generally tend to also have more competition (wider choice of available suppliers for the customer). Customers are likely to be price sensitive because price is the only reasoning point why a customer will buy from one supplier rather than another.

You have to consider such things before deciding to start a business in such an arena. Businesses can and are often successful in price proposition sectors but you must have a clear plan on how you are going to profitably hit the cost points to enable you to compete on price.

Established competition in price-lead markets often have a cost advantage due to established economies of scale. An example is owning expensive mass-production machinery and/or established and effective logistics.

If you want to enter such markets then factoring the required investment (and expected investor returns) can quickly place you at an insurmountable cost disadvantage.

Given the expected lower price response from competition with more experience than you is likely to present you with an unsustainable business proposition: unless of course, you have a cunning plan.

Where buyers are more powerful than suppliers

In some business to business sectors, customers actively encourage supplier convergence (more than one supplier offering similar products or services). If you have three fish & chip shops in a street all offering a similar menu and quality then all that is left is price. Be aware of this when considering a market sector to enter.

In both commodity and supplier convergence markets, price competition and even price wars are therefore more likely.

For both business to business and consumer sectors there is a gravitational force towards supplier convergence. This is because the instinct is to match and emulate the winning competitor. If the differential proposition is not brave enough to challenge and convince the customer then over time, all participating competition will converge (supplier convergence). Then it’s down to price.

You have to assess the extent of orbiting around the current winning competitor and decide how you are going to successfully resist these forces.

That great equaliser: the internet

Profitable opportunities require variables and incomplete information. Where variables become constants and customers have complete information then they will find it easier to make comparisons and consider the only remaining variable of price. The internet enables customers to easily compare prices, which are a lot easier to communicate quickly on screen than propositions: particularly quality or added value propositions.

E-commerce websites selling me-too or like-for-like products often only have few if any differential propositions to enable conversion – typically: delivery cost, delivery time, promotional incentives or the ergonomics of the website.

Competition can quickly see and respond to price movements which means most sectors with similar products find a low optimum price.

Loss leaders – dancing on glass

Sometimes a company may undertake a lost leader campaign. This is when a product is marketed at reduced profit, even near zero profit or loss.

There is usually one of three reasons for a loss-leader strategy.

- End product. Product nearing the end of its life cycle. Dump it in the market and get it off the stock book.

- New product. Launching a new product into the market to gain impact market share.

- Tactical move. A specific tactical move against competition or competitor as part of a wider strategy.

These loss-leader exercises have to be carefully executed with defined tactics and objectives.

Consider these two points

- The plan to exit out of the strategy is crucial.

- It is much easier to lower prices than to raise them.

Considering the above reasons for a loss-leader strategy from the context of exit.

1. End product

From the perspective of the product itself, there is no problem in that the product line is ending. However, setting a precedent of a new lower price expectation in the market for this or similar products may cause problems for any new product you are launching to replace it.

If you plan not to launch a similar product then this strategy can be disruptive to the competition. Although why you would want to do this again requires careful thought. Competition must eat, so it will either graze in a field you are no-longer interested in or come after the same fields you are now in because it has no other choice.

2. New product

Launching a new product into the market to gain impact market share using price can obviously be successful.

Increasing price once you have achieved those market share objectives though can be hard. One key benefit with this strategy is that you can gain economies of scale.

You need to assess the competition in that they may well respond with lower prices once you begin to hurt them. You may end up with lots of stock or equipment, low sales and at a price that simply doesn’t make sense.

3. Tactical moves

Specific tactical pricing against competitors as part of a wider strategy can quickly become a game of chess in a market consisting of intelligent competition. Active competition with its ear to the ground will be responsive – and in that are the tactics. Ironically, the more stupid the competition, the more your tactical pricing may depend on luck.

Be careful instigating price wars

Reducing prices in a zero sum market will simply lead to competition price reactions.

A zero sum market is where there is no additional growth or penetration into new sectors available. The cake isn’t getting any bigger.

Reducing your price will therefore not add new business to the market but instead simply take business from competition. Competition will then likely respond by matching your new low price or even beating it.

This can result in all participants in that market finishing with roughly the same market share as at the beginning but all with lower prices and lower profits.

The sum value of that market is now less than before and is less healthy due to lower profits and increased pressure on costs. This in turn may affect product or service quality and investment.

Internal influencers on cost

Good business obviously requires a positive relationship between cost in and price out.

You can aim for economies of scale (reduced unit costs due to more efficient production and/or logistics) or wider allocation of fixed costs. But be aware of the following traps.

Stepped fixed costs: for example, just when you thought you were getting somewhere on profit, you have to employ two more people.

Cashflow: increased market share usually means more working capital required.